April 20th, 2003.

Ford’s Theatre, Washington, DC.

We crossed down the boards toward the edge of the stage, near where the box hung twelve feet above us. “I put this house back together,” a North Carolina accent rang out from behind me, still thick even after 30 plus years in DC. Tommy Berra, the Technical Director of the Ford’s Theatre, had been part of the team that re-opened the moribund space in 1968, part of a group led by Producing Director Frankie Hewitt. Silver haired and compactly built, I often wondered how Tommy could be so tan, given that he spent so much time inside at Ford’s; but in point of fact he somehow spent every other waking minute on the golf course. Tommy knew every inch of this place, which in addition to being a working professional theatre is also a National Park.

He crossed down and stood next to me. “It was locked up for years just after, you know; they just froze it, boarded it up. Then they tried makin’ a warehouse out of it ’n there was an accident, a bunch of people died… this house was cursed. ’Til we put shows back in here.”

I gestured up to the Lincoln Box, a fixed point in time, a portal to a divided past, which hovers over downstage left, directly over the stage. This is architecture in the old theatre tradition, in which being seen by the rest of the audience mattered far more than having a decent view of the show. “How much of that is original?”

“Not much,” Tommy returned, “I mean the walls are the same, the trim, but everything fabric has been replaced, some of which I did. I remember when when we were working on the place back in ’68, I was up there and got up on a couch to install a light. Well, hold on now, let me back up a little. It was a little dark up in there, and I had forgotten my stepladder, so I just reached around until I found old piece of furniture and moved it under where I needed to be. I climbed up on it and started to work on some wiring. And I’m up there, doin’ my thing, and this woman comes in, she’s giving a tour or something, and starts screaming at me. ‘Get down! Get down!’ …and I’m thinkin’, what, what?”

He paused for effect, his eyes twinkling. “I look down and I see the area near my boots on this old settee was stained, dark black. I’m standin’ on the couch where they laid Old Abe after the shot. That stain was his blood.”

In early March of 2003, I started rehearsals for a production of the musical 1776 at Ford’s; I was to play Thomas Jefferson. Let’s zoom in on that: I, an actor, was to play Thomas Jefferson in a theatrical show about the creation of the United States on the site where John Wilkes Booth, an actor, attempted to destroy the United States by assassinating President Abraham Lincoln while he was watching a theatrical show.

Yeah. The mind boggles.

Our click-thirsty media makes a great deal of ad money by breathlessly proclaiming that the post-mid-Trump America of today is more divided than it has ever been. That statement completely ignores the America of the 1850s-60s, when a state-based pro-slavery movement flipped the bird to the Federal government: “States’ Rights! STATES’ RIGHTS!” rang their rallying cry, which, when run through the truth machine, actually comes out ‘States’ ability to buy and sell people, beat them to death, separate mothers from their children, and also make a great deal of money!’

They forced a Southern secession and one of the bloodiest civil wars in history, quite literally pitting brother against brother. And bloodiest is NOT hyperbole: Twice as many Americans died at the Battle of Gettysburg, in three days, than died in all eight years of the American Revolutionary War.

Separating from England and creating a country? 25,000 dead. Fighting over a small patch of southern Pennsylvania, less than 100 years later? 51,000 sons rotting in the sun of early July.

We are taught, correctly, that Abraham Lincoln was one of the greatest presidents in American history; what we often miss is that in April of 1865, when he was shot in the back of the head and then died, thousands of Americans celebrated, danced in the streets, and partied.

MAGA lames in comparison. They’re closing in, though.

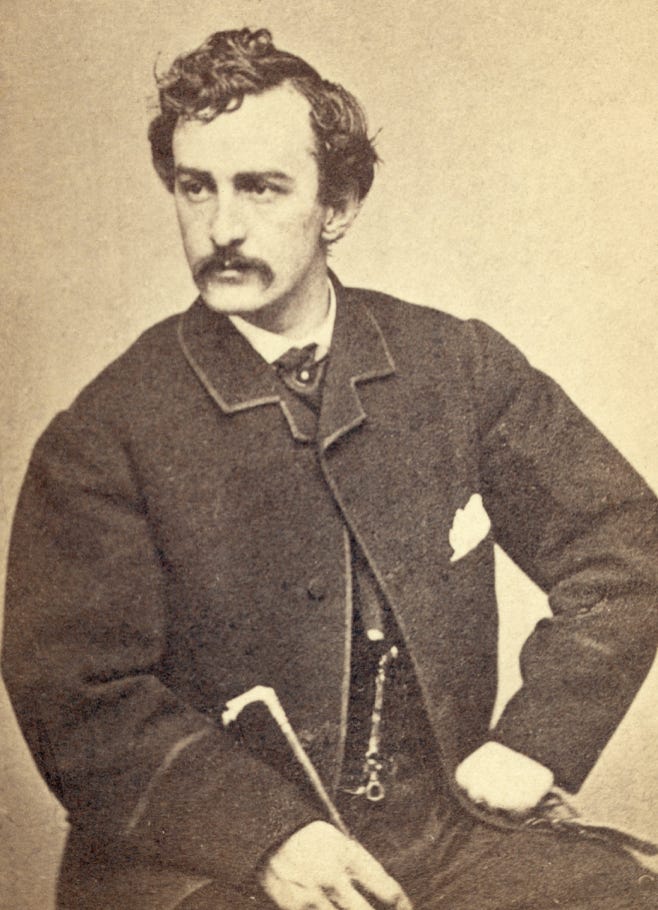

John Wilkes Booth was American Theatre royalty, one of several actor sons of Junius Brutus Booth. Dear Ole Dad is considered by historians to be the first American megastar performer. Junius emmigrated to Maryland from London in 1821, abandoning a wife and child in England along the way, then proceeded to have 10 children with his mistress, John Wilkes being the ninth of the bunch. His wife in England filed for and was granted a divorce on the grounds of adultery and desertion, and Junius married his mistress the year John Wilkes turned 13.

Junius, who had always loved the bottle, devolved along the way into a roaring alcoholic. He was reputed to be a stunningly talented actor but mentally unstable, and he drank to quiet the demons. It got so bad that later in his career, at one performance of Othello, fellow cast members had to rescue the actress playing Desdemona as Booth genuinely tried to suffocate her with a pillow. Another time, when a theater manager locked Junius in his dressing room before a performance to insure his sobriety, Booth bribed a stagehand to go out and buy him whiskey; the stagehand then dangled the bottle outside the dressing room door and Booth stuck a straw through the keyhole, thereby getting his drink on from distance.

Papa Booth was a total a**hole.

Also, people also don’t really understand what a star John Wilkes was; he was a huge heartthrob, considered the Brad Pitt of his day (if Brad Pitt were a racist Confederate state’s rights advocate). Mail from swooning fans of both sexes followed him from theatre to theatre around the country. Booth genially waved to theatre management as he’d walked backstage at the Ford’s on the evening of April 14th, 1865. How did he get in so easily? He’d performed and ‘gotten his mail there’ in the past, and owner John T. Ford was a family friend - the staff there all knew him.

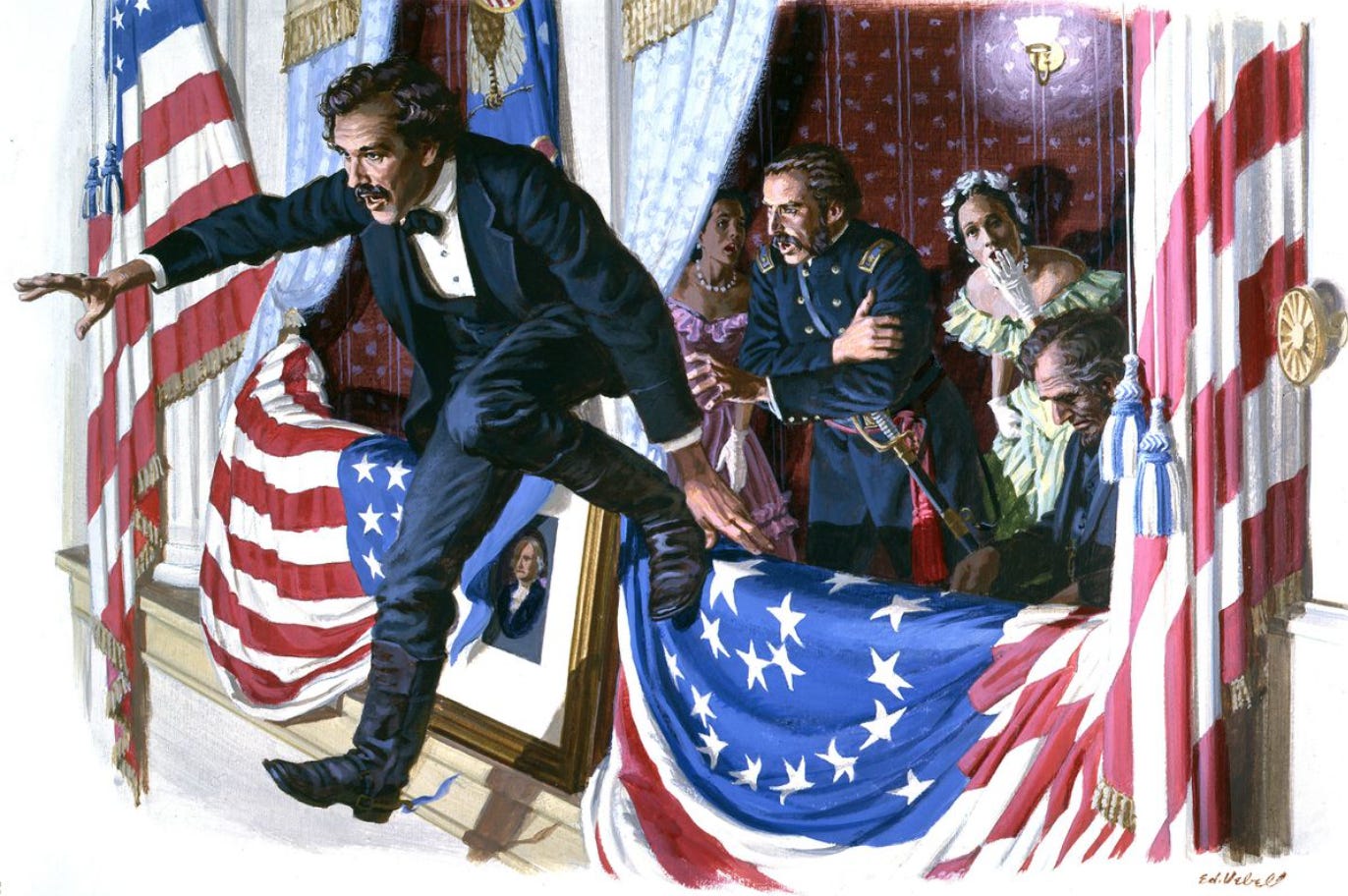

At around 10:10pm during the third act of Our American Cousin, Booth quietly found his way out into the house, crept into the President’s box, and fired a single shot to the back of Lincoln’s head with a Deringer pistol. Major Henry Rathbone, one of the Lincolns’ guests that evening, lunged for Booth. John Wilkes managed to pull his knife and stab Rathbone in the arm, and then in the confusion launched himself from the box to the stage. He landed awkwardly on the boards, fracturing his ankle; adrenaline pumping, he righted himself, brandished the knife and glared at the shocked audience. “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” he shouted, (‘Thus always to tyrants!’ - from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar) and bolted for the the back alley where a getaway horse was waiting. Some of the audience actually thought this whole sequence was part of the show.

(I’ve always wanted to write ‘getaway horse’, by the way. I do believe that this is a phrase we should get back to.)

Lincoln was taken gingerly across the street to a boarding house, where in spite of a bullet to the brain and a great loss of blood, he hung on in a coma for nearly 8 hours before passing. Through the night, thousands gathered outside in vigil on 10th Street NW.

The authorities caught up with Booth twelve days later in Northern Virginia, cornering him in a barn. When he refused to come out and end the standoff, they set the barn on fire, then shot him in the neck as he drew a pistol and tried to escape the flames. Paralyzed, he died a few hours later.

So from day one of this particular job, from Jefferson to the Lincoln Box, I was steeped in history - DC drips with it, good and bad. And, thanks to

Director David Bell’s wonderful casting and leadership, I was also stewing in burgeoning friendships: Kate Baldwin, who played opposite me as Martha Jefferson, met her future husband Graham Rowat on that show; Lewis Cleale played John Adams better than it’s been played since William Daniels. Also in that company was a talented tenor named Mark Aldrich, who would one day become the one and only “Historian Guy” of The Happy Hour Guys, my producing partner and one of my best friends. Mark grew up in Boston and DC, knew both areas well, and true to his Irish heritage, was born to sing like an angel and sit at a bar.

We spent our costumed hours of 1776 wearing our Revolutionary finery, with buckles on our shoes and wigs on our heads, doing a show that I consider to be one of the best written musicals in the canon. In our non-costumed hours, Mark and I began running into each other at various great historic bars in DC. Over and over again. Our cast was very social - whether we were heading to a downtown pub after showtime or out to Tommy’s V.A. chapter in Virginia for Karaoke Nights, these folks loved each other’s company. Laughter and fellowship was our currency, and we spent freely. This is not always the case, but very welcome when it does happen, especially with Actors who are working out of town.

And the possibilities to socialize seemed endless; DC does not lack for terrific pub culture. Look no further than Old Ebbitt Grill.

Old Ebbitt is, to some peoples’ reckoning, the oldest bar in DC - our friends Honest Abe and John Wilkes likely had drinks there, though surely not at the same time. Established some time around 1856 as an unnamed restaurant in the Old Ebbitt Hotel, Ebbitt has gone through various incarnations (and buildings) since then, now on 15th Street NW across from the Treasury Department. Clad in dark wood, lit with brass and tiffany lamps and festooned with game trophies, Old Ebbitt calls out to the cool and sneaky in all of us. Even on a busy evening, walking in to the place and sitting at one of the several gorgeous bars makes one feel like you might be about to hold court, lay out a fantastic plan, or meet a mistress. Some of the game trophies on the walls are reputed to have been shot (but not stuffed) by Teddy Roosevelt. And Old Ebbitt has hosted party scandals that run the gamut from merely political to downright cinematic - in the 1970s a Soviet Spy ring used it as a meeting place. I’m thinking that that gives ‘talking into your beer’ a whole new meaning.

The peril of divided drinking takes on corporeal form in a pub as steeped in history as Old Ebbitt. Because in such a bar you have two very distinct choices: Hide, or Be Social. My definition of pub culture includes 98% the latter and about 2% the former. In the best of times we go to the bar to have a laugh, listen to music, and possibly buy a drink for a stranger, expand our circle and our world. In the worst of times we keep our circle small and exclusive; or worse, we hunker alone and spiral down a well of something ugly.

Old Ebbitt is a living museum of what’s possible when we drink socially.

I love museums, but tend to get ‘museum head’ (a.k.a. ‘Jimmy’s nap time’) after two hours or so - however, as a patron in a historic bar, I could loll around for many more and barely notice the little hand sweeping around the clock face. Perhaps the availability of comfortable seating, beer and food has something to do with it? This warrants more study.

Did John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators meet in taverns to discuss their plans to kill Honest Abe? Surely they did. While they were planning, they feel like the heroes of the American revolution, firebrands like Thomas Paine? Perhaps. But their drinking in these hypothetical taverns was separate; they sat in the corner, scheming, shielded, anti-everything but themselves. That is not pub culture; that is division. And historic pubs teach the lessons of division: Old Ebbitt’s very walls house the echoes of over one and a half centuries of fellowship and heartbreak. How much laughter has cascaded here, for every conceivable reason? And how many tears were shed in the days and months after April 14th, 1865? Surely they ran down the bar in waves.

Find a historic pub, sit down, order, and listen. The echoes whisper, murmur, even shout at us - tell us to reach out, and cross the breach. They demand that we note, in sometimes excruciating detail, the interplay of history and fellowship; what happens when they coincide, and what happens when they divide.

Divided drinking killed Abraham Lincoln.

“What happened after that?” I asked Tommy, as he finished his stage check before heading back to his office. He turned to me. “After what?”

“After she got you down off of the settee. When you were in the Box, that day in ‘68.”

“Oh, I think I went and got my step ladder and finished the job right,” he said. His brow furrowed. “Wait, now. You asked if anything was original up there, right?”

“Yeah. You said not much.”

He smiled. “Yeah, not much at all. Except for this.” He moved down to extreme downstage left, just under the Box, and pointed up. Adorning the front was a framed portrait of George Washington. Tommy grinned. “Do you see ‘ole George?”

“Yeah,” I answered, “Funny, I’ve always wondered about that. Why is he up there, if it’s the Lincoln Box?”

Tommy was a beloved uncle delving further into a family tale. “Well, the decision to come to the theatre that night was a last minute one. The President and his wife invited a bunch friends to join, and no one was available it was so quick. But they finally found found some folks, Major Rathbone and his wife, and sent word that they were coming to the theatre quite late in the day. So the manager here didn’t have much time to prepare for their arrival. They threw up the bunting, a nice gesture, but I guess it didn’t seem presidential enough, and the manager wanted folks to know that the president was in the house. And - whoops! - they didn’t have a portrait of old Abe. So the story is that somebody found that portrait of George and they threw it up there.”

I squinted up, shaking my head. “Huh. I don’t know, man. Do you think that’s true? How can you be sure that’s even the same portrait?”

And there was that same twinkle in his eyes again. “Well…” he pointed up. “See the edge of the frame there up on the top right? Look close.”

I gazed up at the frame. Near the top right corner of the gilt edge, there was a small chunk missing, like a tooth from a golden smile. I hadn’t noticed it before, but if I had, I would have just chalked it up to the age of the wood.

“Yeah, I see it,” I said.

Tommy nodded. “An old timer once told me that when Booth vaulted over the edge of the box rail towards the stage, he got caught in the bunting and fell all off-kilter, and I think that’s true. Because he would’ve been wearing his spurs, so he could push that horse he had stashed out there, push it to get away as quick as possible, and them spurs woulda gotten caught. That chip there? That’s where his spur clipped the edge of the picture on the way down.”

I shook my head, looked back up at the frame, and took a long breath. Hide, or Be Social. The theatre breathed back, expectant.

“Tommy,” I murmured, “May I borrow your stepladder?”

Find (and drink) your history in DC:

- Ford’s Theatre, 10th St NW, Washington, DC 20004

You owe it to yourself. Just go. Spend the afternoon in the museum, take a tour, and then see whatever is playing that night. Great restaurants right across the street, and Old Ebbitt’s is just a few blocks away. Laughter: Hushed, unless there’s a comedy playing.

- Old Ebbitt Grill, 675 15th St NW, Washington, DC 20005

Summed up above. Another can’t-miss in DC for both history and excellent pub culture. Try the oysters, and if you’re around for Oyster Riot, it’s incredible. Go. Laughter: Partisan, and expensive.

- The Bier Baron Tavern (Brickskeller), 1523 22nd St NW, Washington, DC 20037

Nestled into the basement of the historic Marifex Hotel and established in 1957 and originally named the Brickskeller, this venue introduced the District to beer flavor decades before craft beer was even a thing. The Brickskeller’s last night of operation was December 18th, 2010; ownership changed hands and now the tavern has been renamed the Bier Baron. They still celebrate beer there, and it’s well worth a visit: But I miss the old place. Only open 4 days a week post-pandemic, now sharing their space with a comedy club; check their website. Laughter: Plentiful.

- Church Key, 1337 14th St NW, Washington, DC 20005

Built in 2009 above Birch & Barley restaurant, Church Key is the go-to for cutting edge beer in what is now a nation-leading craft beer scene that includes Maryland, Virginia, and DC. Consistently rated by craft beer nerds as one of the best beer bars on the planet, with 50 tap lines and 500 different bottles occupying 3 different climate-controlled cellars, Church Key is a must visit if you’re at all into beer. You’ll learn something. I always do. CK closed during the pandemic and are still closed, after deciding to take the time to do some upgrades before they reopen. Their website says SOON. Laughter: Nerdgasms.

See you in a few weeks.

What great historical context Jimmy. And thanks for the 1776 nod, I am pretty partial to it too!